I've often wondered who is the most famous Roman of them all - Pontius Pilate or Julius Caesar. Pilate has got to be one of the best known to Christians, and millions recite his name every week, if they happen to belong to a denomination that recites the Nicene Creed regularly. But outside Christian culture, Julius Caesar must be the best known Roman of all time. In addition to a month which either he or Augustus had named after himself (July), he's had all sorts of things named after him, from political positions (Kaiser, Tsar) to methods of child delivery, to salads.

Friday, March 16, 2012

(Belated) Ides of March

Wednesday, May 05, 2010

bella stellaria

- How Star Wars history is like Roman History

- Star Wars trailer in Latin (judging from the spelling this one was put together by someone from Finland)

- George Lucas likes Rome (the HBO series that is; interesting because the article suggests his interest in and knowledge of Ancient Rome is quite developed)

- Why Yoda talks funny

- A Latin speech about Star Wars

Tuesday, September 01, 2009

iam ver egelidos refert tepores

Diffugere nives, redeunt iam gramina campis

arboribus comae;

mutat terra vices et decrescentia ripas

flumina praetereunt;

Gratia cum Nymphis geminisque sororibus audet

ducere nuda chorus.

The snows have fled, now the grass returns to the fields, and to the trees their leaves, the earth changes in turn and the swelling rivers flow past their banks, the naked Grace, along with the Nymphs and her twin sisters dares to lead the dance.

Thursday, August 06, 2009

mea columba

Monday, March 16, 2009

Beware...

Assidentem conspirati specie officii circumsteterunt, ilicoque Cimber Tillius, qui primas partes susceperat, quasi aliquid rogaturus propius accessit renuentique et gestu in aliud tempus differenti ab utroque umero togam adprehendit; deinde clamantem: "Ista quidem vis est!" alter e Cascis aversum vulnerat paulum infra iugulum.

As he took his seat, the conspirators gathered about him as if to pay their respects, and straightway Tillius Cimber, who had assumed the lead, came nearer as though to ask something; and when Caesar with a gesture put him off to another time, Cimber caught his toga by both shoulders; then as Caesar cried, "Why, this is violence!" one of the Cascas stabbed him from one side just below the throat.

Caesar Cascae brachium arreptum graphio traiecit conatusque prosilire alio vulnere tardatus est; utque animadvertit undique se strictis pugionibus peti, toga caput obvolvit, simul sinistra manu sinum ad ima crura deduxit, quo honestius caderet etiam inferiore corporis parte velata.

Caesar caught Casca's arm and ran it through with his stylus, but as he tried to leap to his feet, he was stopped by another wound. When he saw that he was beset on every side by drawn daggers, he muffled his head in his robe, and at the same time drew down its lap to his feet with his left hand, in order to fall more decently, with the lower part of his body also covered.

Atque ita tribus et viginti plagis confossus est uno modo ad primum ictum gemitu sine voce edito, etsi tradiderunt quidam Marco Bruto irruenti dixisse: καὶ σὺ τέκνον; Exanimis diffugientibus cunctis aliquamdiu iacuit, donec lecticae impositum, dependente brachio, tres servoli domum rettulerunt.

And in this wise he was stabbed with three and twenty wounds, uttering not a word, but merely a groan at the first stroke, though some have written that when Marcus Brutus rushed at him, he said in Greek, "You too, my child?" All the conspirators made off, and he lay there lifeless for some time, and finally three common slaves put him on a litter and carried him home, with one arm hanging down.

Related Posts

Saturday, February 14, 2009

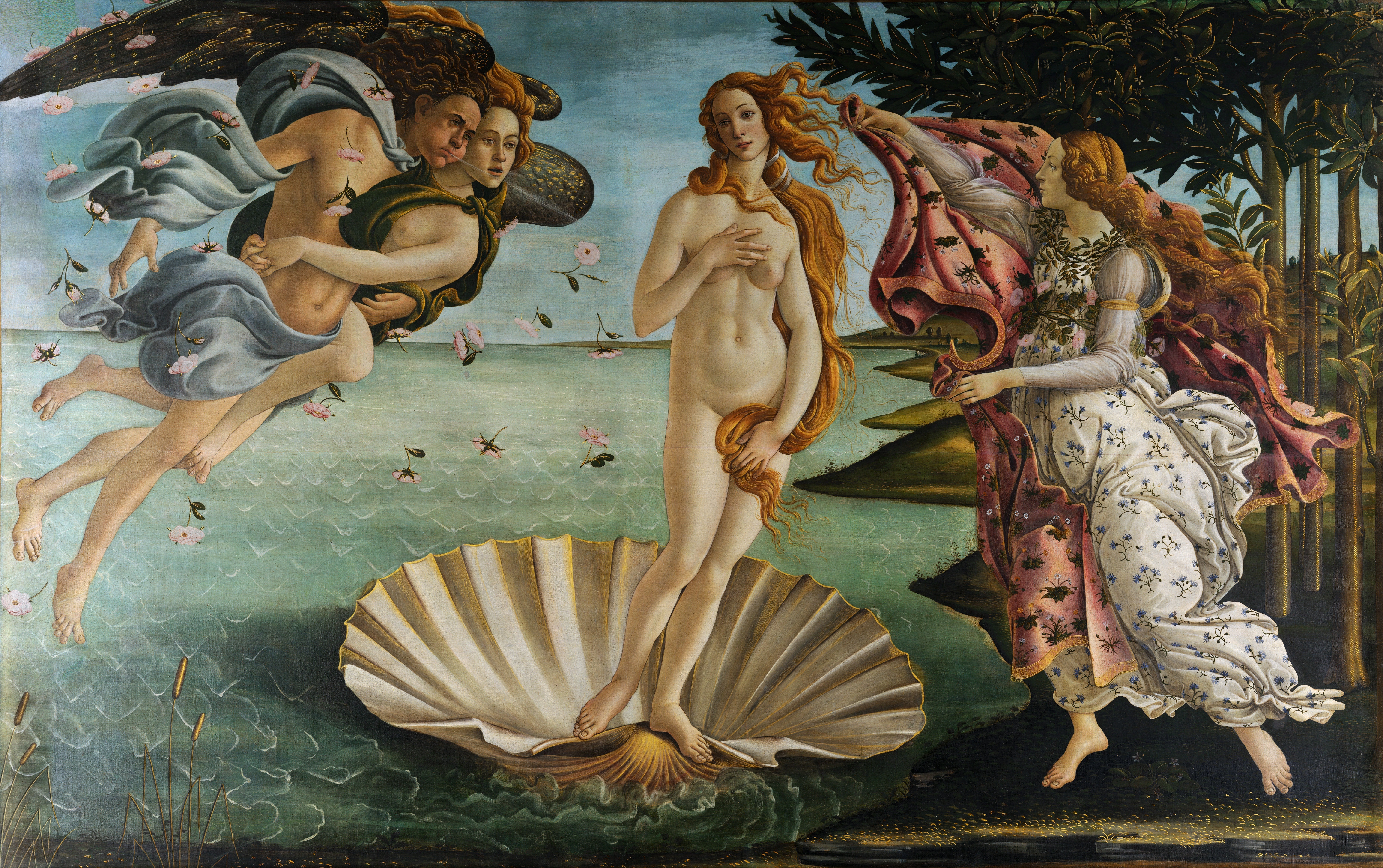

templum Veneris

...in the temple of Venus you might have seen, created upon the wall, in imagery piteous to behold, the broken sleeps and cold sighs, the sacred tears and lamentations, the fiery pangs of desire that love's servants endure in this life... Pleasure and Hope, Desire and Foolhardiness, Beauty and Youth, Mirth, Riches, Love-charms and Violence, Deceits, Flattery, Extravagance, Anxiety and Jealousy... were painted by order upon the wall, and more than I can make mention of.

In truth all the mount of Citheron, where Venus has her principal dwelling, was drawn upon the wall, with all the garden and the lustiness of it. Idleness, the porter, was not forgotten, nor Narcissus the fair of long ago, nor the folly of King Solomon, nor yet the great strength of Hercules; the enchantments of Medea and Circe, nor the hardy fierce heart of Turnus, nor the rich Croesus, captive and in servitude. Thus may you see that neither wisdom nor riches, beauty nor cunning, strength nor hardihood can hold rivalry with Venus, for she can guide all the world as she wish. Lo, all these folk were so caught in her snare until for woe they cried often "Alas!" One or two examples shall suffice here, though I could explain a thousand more.

The naked statue of Venus, glorious to look upon, was floating in a great sea, and from the navel down all was covered with green waves, bright as any glass. She had a lyre in her right and, and on her head a rose-garland, fresh and fragrant, and seemly to see. Above her head fluttered her doves, and before her stood her son Cupid, blindfolded, as he is often shown, with two wings upon his shoulders. He carried a bow and bright, keen arrows.

Monday, April 28, 2008

Anzac Day

By the time of the Great War, glamorous myth had replaced hard-edged history as another armada sailed for the Hellespont. The Englishman Patrick Shaw-Stewart, combatant and classicist, took an old copy of Herodotus on the boat to Gallipoli. ‘The flower of sentimentality expands childishly in me on classical soil,’ he wrote. ‘It is really delightful to bathe in the Hellespont looking straight over to Troy’...

The much-loved Rupert Brooke, sailing to the Dardanelles- he was to die off Skyros of an untreated mosquito bite two days before the dawn landing of 25 April 1915- also pictured the impending battle in the colours of a glorious past:

They say Achilles in the darkness stirred…

And Priam and his fifty sons

Wake all amazed, and hear the guns,

And shake for Troy again.

The officers and soldiers of the Australian Imperial Force were hardly immune to the resonance of their surroundings. An Australian contingent, pushing out their trenches at Gallipoli, chipped away at the buried remains of an ancient settlement, but there was no time for amateur archaeology and enemy fire propelled them on. Charles Bean, the classically educated war correspondent and official military historian, later kicked at the dirt and uncovered a coin of ancient provenance. The Australians may not have penned war poetry of lasting merit, but their waggish doggerel offers a distinctly ironic counter to the high-toned myth of war:

An then ol’ Joe- ‘e was a well read chap-

Starts tellin’ us about a ten years scrap

They ‘ad in Troy which wasn’t far away

So Joe made out, from where we were that day.

A bloke ‘ad pinched a bonzer tabby, then

‘Er own bloke came to get ‘er back again,

An all ‘is cobbers came to see fair play,

An’ in the end they got ‘er safe away.

But Bill ‘e didn’t think a scrap could start

And last ten years about a blanky tart;

No Jane ‘e’d ever met was worth a brawl.

There must be something else behind it all.

Within a few short years of the homecoming the Anzac experience of blood, mud, and gore had been burnished into the much more brilliant Anzac legend; the hard-bitten Australian digger was openly likened to both the Greek citizen-soldier and the Homeric warrior of myth. For the author of The Trojan War 1915, a member of the Australian Field Ambulance on Gallipoli, the digger was already a reincarnated Greek hero:

Homeric wars are fought again

By men who like old Greeks can die;

Australian backblock heroes slain

With Hector and Achilles lie.

Tuesday, April 22, 2008

dies romae natalis

April 21st, 753 B.C. is the traditional date for the founding of the city by Romulus and Remus; this is how Livy recounts events:

Ita Numitori Albana re permissa Romulum Remumque cupido cepit in iis locis ubi expositi ubique educati erant urbis condendae...

Romulus and Remus, after the control of Alba had passed to Numitor in the way I have described, were suddenly seized by the desire to found a new settlement on the spot where they had been exposed and subsequently brought up...

Intervenit deinde his cogitationibus avitum malum, regni cupido, atque inde foedum certamen coortum a satis miti principio.

Unhappily the brothers' plans for the future were marred by the same source which had divided their grandfather and Amulius- a lust for power. A disgraceful quarrel arose from a matter in itself trivial.

Quoniam gemini essent nec aetatis verecundia discrimen facere posset, ut di quorum tutelae ea loca essent auguriis legerent qui nomen novae urbi daret, qui conditam imperio regeret, Palatium Romulus, Remus Aventinum ad inaugurandum templa capiunt.

Since they were twins and no distinction of age could be made between them, they determined to ask the gods under whose care those places were, to declare by means of augury who should govern the new city, once it had been founded, and give his name to it. Romulus took to the Palatine Hill, Remus to the Aventine, in order to take the auguries.

Priori Remo augurium venisse fertur, sex voltures; iamque nuntiato augurio cum duplex numerus Romulo se ostendisset, utrumque regem sua multitudo consalutauerat: tempore illi praecepto, at hi numero auium regnum trahebant. Inde cum altercatione congressi certamine irarum ad caedem vertuntur; ibi in turba ictus Remus cecidit.

Remus, so the story goes, was the first to receive a sign- six vultures; and no sooner was this announced than double the number of birds appeared to Romulus. The followers of each promptly hailed their own master as king, one side basing its claim upon priority, the other upon number. Angry words ensued, followed by blows, their anger turned to violence, and there, in the crowd, Remus was struck and fell down dead.

Volgatior fama est ludibrio fratris Remum novos transiluisse muros; inde ab irato Romulo, cum verbis quoque increpitans adiecisset, "Sic deinde, quicumque alius transiliet moenia mea," interfectum. Ita solus potitus imperio Romulus; condita urbs conditoris nomine appellata.

There is another, more common story, that Remus, making fun of his brother, jumped over the newly-built walls, whereupon Romulus killed him in a fit of rage, adding the threat, 'So perish whoever else shall overleap my battlements.' In this way Romulus gained sole possession of power; the city, having been founded, was took its name from its founder.

Thursday, January 03, 2008

Happy Birthday

One of my favourite works of Cicero is De Senectute (On Old Age). Cicero lived to be 63, not a bad effort in Roman times, and would have lived even longer had he not fallen foul of Marc Antony who had him killed. Here is the opening to De Senectute, framed as a conversation between Marcus Porcius Cato, Scipio Amelianus and Gaius Laelius:

Scipio: Saepe numero admirari soleo cum hoc C. Laelio cum ceterarum rerum tuam excellentem, M. Cato, perfectamque sapientiam, tum vel maxime quod numquam tibi senectutem gravem esse senserim, quae plerisque senibus sic odiosa est, ut onus se Aetna gravius dicant sustinere.

Cato: Rem haud sane difficilem, Scipio et Laeli, admirari videmini. Quibus enim nihil est in ipsis opis ad bene beateque vivendum, eis omnis aetas gravis est; qui autem omnia bona a se ipsi petunt, eis nihil malum potest videri quod naturae necessitas adferat. Quo in genere est in primis senectus, quam ut adipiscantur omnes optant, eandem accusant adeptam; tanta est stultitiae inconstantia atque perversitas. Obrepere aiunt eam citius, quam putassent. Primum quis coegit eos falsum putare? Qui enim citius adulescentiae senectus quam pueritiae adulescentia obrepit? Deinde qui minus gravis esset eis senectus, si octingentesimum annum agerent quam si octogesimum?

Scipio: Laelius and I often express admiration for you Cato. Your wisdom seems to us outstanding, indeed flawless. But what strikes me particularly is this. I have never noticed that you find it wearisome to be old. That is very different from most other old men, who claim to find their old age a heavier burden than Mount Etna itself.

Cato: You are praising me for something which, in my opinion, has not been a very difficult achievement. A personwho lacks the means within himself, to live a good and happy life will find any period of his existene wearisome. But rely for life's blessings on your own resources, and you will not take a gloomy view of any of the inevitable consequence's of nature's laws. Everyone hopes to attain an advanced age; yet when it comes they all complain! So foolishly inconsistent and perverse can people be.

Old age, they protest, crept up on them more rapidly than they had expected. But, to begin with, who was to blame for their mistaken forecast? For age does not steal upon adults any faster than adulthood steals upon children. Besides if they were approaching eight hundred instead of eighty, they would complain of the burden just as loudly!(Cicero, De Senectute, 4)

Thursday, December 20, 2007

Saturnalia

- The timing; Saturnalia was not on exactly the same date as Christmas, but it was in late December (17th-23rd) which is close enough.

- The food; Saturnalia was celebrated with lots of eating and drinking, just like Christmas is today (at least in my family).

- The presents; Romans gave each other small gifts at the time of the festival. The poet Martial mentions as presents a pig, a parrot, dice, knuckle bones, moneyboxes, combs, toothpicks, a hat, a hunting knife, an axe, lamps, balls, perfumes, pipes, a sausage, tables, cups, spoons, items of clothing, statues, masks, and books (among other things).

But what characterised Saturnalia most of all was the role reversal of slave and free. Freeborn Romans would wear the pileus- a hat usually only worn by freedmen, and slaves would recline at luxurious banquets, waited upon by their masters. During this time slaves were also permitted to gamble, and could not be punished by their masters. It was a time of general relaxation, enjoyment and hilarity, much enjoyed by the Roman people- Catullus calls Saturnalia the best of days (die... optimo dierum) and attempts by the emperors Augustus and Caligula to shorten the celebrations failed, due to overwhelming popular support.

Here are two Roman accounts of Saturnalia, one from Seneca the younger, the other from Macrobius:

December est mensis: cum maxime civitas sudat. ius luxuriae publice datum est; ingenti apparatu sonant omnia, tamquam quicquam inter Saturnalia intersit et dies rerum agendarum.

It is now the month of December, when the whole city sweats. The right of luxury is given to all people; everywhere you can hear the sound of great preparations, as if there were some real difference between the days devoted to Saturn and those for doing normal business.(Epistulae Morales II.XVIII)

inter haec servilis moderator obsequii ammonet dominum familiam pro sollemnitate annui moris epulatam. hoc enim festo religiosae domus prius famulos instructis tamquam ad usum domini dapibus honorant: et ita demum patribus familias mensae apparatus novatur.

Meanwhile the head of the slave household came to tell his master that the household had feasted according to the annual ritual custom. For at this festival, in houses that keep to proper religious usage, they first of all honour the slaves with a dinner prepared as if for the master; and only afterwards is the table set again for the head of the household.(Saturnalia I.XXIV.22)

Monday, August 20, 2007

mors Augusti

Yesterday marked (if my calculations are correct) 1,993 years since the death of Rome's first Emperor, Augustus Caesar. Augustus wasn’t his really his proper name- he was born Gaius Octavius, but when he was adopted by Julius Caesar he changed his name (according to Roman custom) to Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, from where his other well known name – Octavian – comes.

Yesterday marked (if my calculations are correct) 1,993 years since the death of Rome's first Emperor, Augustus Caesar. Augustus wasn’t his really his proper name- he was born Gaius Octavius, but when he was adopted by Julius Caesar he changed his name (according to Roman custom) to Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, from where his other well known name – Octavian – comes.The name Augustus itself is more of a title than a name- it means something like ‘sacred’ or ‘majestic’, and was granted to him by the Roman senate after his victory over Marc Antony and Cleopatra. Here's how the Roman biographer and historian Suetonius described his death:

Supremo die identidem exquirens an iam de se tumultus foris esset, petito speculo, capillum sibi comi ac malas labantes corrigi praecepit, et admissos amicos percontatus [est] ecquid iis videretur mimum vitae commode transegisse... Omnibus deinde dimissis, dum advenientes ab urbe de Drusi filia aegra interrogat, repente in osculis Liviae et in hac voce defecit: "Livia, nostri coniugii memor vive, ac vale!" sortitus exitum facilem et qualem semper optaverat...

On his last day, he would ask now and then if there was any disturbance in the forum on his account, and calling for a mirror, he ordered his hair to be combed, and his hollow cheeks to be adjusted and he enquired of his friends, who were there, if he seemed to them to have performed life's play well enough... Then, having dismissed them all, while he was questioning some who had just arrived from the city, about Drusus's sick daughter, he suddenly died, amidst the kisses of Livia, and with this cry: "Livia! Live with the memory of our marriage; and now, farewell!" having been granted an easy death, and of such a kind as he had always wished for.

[Suetonius, Divus Augustus 99]

Tuesday, March 27, 2007

servi

Last Sunday marked 200 years since the British parliament, after almost twenty years campaigning by William Wilberforce and John Newton (amongst of course many others) passed an act to abolish slavery.

Here are six things you might not have known about slavery in Roman times:

- In the early Roman Empire, at a time when the population of the city of Rome alone was approximately one million, slaves made up approximately 15-20% of the population - and no one is quite sure where the Romans got them all.

- There were many ways to become a slave- you could be born into slavery, taken prisoner in battle, or kidnapped by pirates. Babies who had been abandoned by their parents were also often brought up as slaves, or you could sell yourself into slavery to pay a debt.

- Slaves had no rights under Roman law, and were treated as property rather than as people. They could not own property, they could not marry, and they could be put to death by their master without trial. If a slave had a child, the child would belong to the slave’s master.

- At the same time, many slaves were given positions of power and responsibility in their masters’ homes. For example, Cicero owned a slave called Tiro, who acted as his secretary, editor and publisher. Their relationship seems to have been one even of friendship. Seneca also records for us that masters who were cruel to their slaves were often publicly insulted.

- There were three main ways to free a slave. Firstly a master could simply list his slave as a person (rather than as property) in the census that came around every five years. Secondly, he could go to court and declare that the slave did not belong to him. If no-one objected the slave was free. Thirdly, he could set a slave free in his will.

- There was little stigma attached to being an ex-slave (libertus). Liberti could not run for public office themselves, nor join the army, but they were allowed to vote in the public assemblies, and their children were permitted the full rights of a civis Romanus. Horace was the son of a libertus, as was Publius Helvius Pertinax, who succeeded Commodus as Emperor. Masters would often help to set up their freedmen in business, and were obliged to maintain a patron-client relationship with them. Some liberti, with the help of their former masters, were even able to become very successful and wealthy.

This site has more, and much better, information.

Friday, March 16, 2007

Beware the Ides of March!

- Caesar’s family claimed that they were descended from the goddess Venus, through the Trojan hero Aeneas and his son Iulus (from whom their family derived their name).

- The name Caesar has a number of possible derivations. Probably the most well known is that the first Caesar was born by Caesarean section (Latin caedo, caedere, caesi- to cut). Other suggestions include that the first Caesar killed an elephant (caesai in Moorish) in battle; that he had a thick head of hair (Latin caesaries); that he had bright grey eyes (Latin oculis caesiis).

- He may have had epilepsy. Suetonius and Plutarch both record seizures, and Shakespeare mentions it in his tragedy Julius Caesar.

- Caesar was once kidnapped by pirates, who demanded a ransom of 20 talents of gold. Caesar was insulted by such a small sum, and demanded that the pirates raise their price to fifty talents.

- During the Catilinarian conspiracy, Caesar argued that the conspirators should be imprisoned rather than executed. During the senate’s deliberations, a slave brought came in with a note for Caesar. Cato, Caesar’s great adversary, accused him of being in league with the conspirators, and demanded that the note be read aloud. The note turned out to be a love-letter from Cato’s half-sister.

And three things Caesar (is supposed to have) said:

alea iacta est- the die is cast.

Caesar is supposed to have said this when he crossed the Rubicon with his army, initiating civil war with Rome. He meant that he had passed a point of no return- he had thrown the dice and now had to wait and see what the consequences would be. It’s unclear whether Caesar actually said this, or whether Suetonius made it up to add a bit of drama. If he did say it he probably said it in Greek anyway, as it’s a reference to a play by Menander.

veni vidi vici- I came, I saw, I conquered.

Apparantly Caesar said this to the senate after putting down a rebellion in Pontus (near the black sea). At the time Caesar was in the middle of a civil war, and so his nonchalance was calculated to remind the senate of his military strength.

et tu Brute?- not you too, Brutus?

Caesar’s final words (as his friend Brutus stuck the knife in) according to Shakespeare- but what would he know? Suetonius reports Caesar’s words (still addressed to Brutus) as ‘You too, my child?’ (in Greek), while Plutarch says that Caesar simply pulled his toga over his head in grief at seeing Brutus among the conspirators.

Wednesday, February 14, 2007

Happy Valentine's Day

At this time many of the noble youths and magistrates run up and down through the city naked, for sport and laughter striking those they meet with strips of goat hide. And many women purposely get in their way, and like children at school present their hands to be struck, believing that the pregnant will thus be helped in delivery, and the barren to pregnancy.

The festival was called the Lupercalia (from the Latin word lupus, wolf), and the ritual may also be connected with the legendary wolf that raised Romulus and Remus.

In any case, in honour of St Valentine (whoever he may or may not have been), here’s part of a poem from Ovid, describing his own experience of love:

esse quid hoc dicam, quod tam mihi dura videntur

strata, neque in lecto pallia nostra sedent,

et vacuus somno noctem, quam longa, peregi,

lassaque versati corporis ossa dolent?

nam, puto, sentirem, siquo temptarer Amore.

an subit et tecta callidus arte nocet?

sic erit; haeserunt tenues in corde sagittae,

et possessa ferus pectora versat Amor.

cedimus, an subitum luctando accendimus ignem?

cedamus! leve fit, quod bene fertur, onus.

vidi ego iactatas mota face crescere flammas

et rursus nullo concutiente mori.

[Ovid, Amores I.2]

What is happening to me? My bed seems so hard, my blankets don’t sit straight on my bed,

Surely I would have felt it, if I were the victim of some attack of Love- or has he snuck up on me, and done his damage by secret trickery?

Do I give in, or do I feed this unexpected flame by struggling? Let me give in: a burden readily borne becomes light.

I have seen flames blaze up, fanned by shaking a torch, and I have seen them die when left alone.

[But is Ovid really in love? He’s caught the fever, but doesn’t realise at first, doesn’t actually ever mention a girl. He asks whether he should give in to love, but the eagerness of his acquiescence makes us suspicious of his sincerity. The love he describes also fits all the clichés (a fever, a fire, a struggle, torture) a bit too neatly. He seems rather to be in love with the idea of Love, or even with the idea of being a Love poet.]

Monday, December 18, 2006

On this day...

Today is the anniversary of the Battle of Trebia, the first major battle fought by Hannibal against the Romans in the Second Punic War. Hannibal had crossed the Alps from Spain into Italy with an army of some 40 000 men, and Tiberius Sempronius Longus (eager for battle with an election approaching) foolishly walked his larger army straight into an ambush. Here is Livy’s account of the battle:

Today is the anniversary of the Battle of Trebia, the first major battle fought by Hannibal against the Romans in the Second Punic War. Hannibal had crossed the Alps from Spain into Italy with an army of some 40 000 men, and Tiberius Sempronius Longus (eager for battle with an election approaching) foolishly walked his larger army straight into an ambush. Here is Livy’s account of the battle:Sempronius ad tumultum Numidarum primum omnem equitatum, ferox ea parte virium, deinde sex milia peditum, postremo omnes copias ad destinatum iam ante consilio avidus certaminis eduxit.

Sempronius, eager for the contest, as soon as battle was provoked by the Numidians, led out all the cavalry, being full of confidence in that part of the forces; then six thousand infantry, and lastly all his army, to the place already determined in his plan.

erat forte brumae tempus et nivalis dies in locis Alpibus Appenninoque interiectis, propinquitate etiam fluminum ac paludum praegelidis. ad hoc raptim eductis hominibus atque equis, non capto ante cibo, non ope ulla ad arcendum frigus adhibita, nihil caloris inerat, et quidquid aurae fluminis appropinquabant, adflabat acrior frigoris vis.

It happened to be the winter season and a snowy day, in the region which lies between the Alps and the Apennine, and excessively cold by the proximity of rivers and marshes: besides, there was no heat in the bodies of the men and horses thus hastily led out without having first taken food, or employed any means to keep off the cold; and the nearer they approached to the blasts from the river, a keener degree of cold blew upon them.

ut vero refugientes Numidas insequentes aquam ingressi sunt—et erat pectoribus tenus aucta nocturno imbri—tum utique egressis rigere omnibus corpora ut vix armorum tenendorum potentia esset, et simul lassitudine et procedente iam die fame etiam deficere.

But when, in pursuit of the flying Numidians, they entered the water, (and it was swollen by rain in the night as high as their breasts,) then in truth the bodies of all, on landing, were so benumbed, that they were scarcely able to hold their arms; and as the day advanced they began to grow faint, both from fatigue and hunger.

Hannibalis interim miles ignibus ante tentoria factis oleoque per manipulos, ut mollirent artus, misso et cibo per otium capto, ubi transgressos flumen hostes nuntiatum est, alacer animis corporibusque arma capit atque in aciem procedit…

In the mean time the soldiers of Hannibal, fires having been kindled before the tents, and oil sent through the companies to soften their limbs, and their food having been taken at leisure, as soon as it was announced that the enemy had passed the river, seized their arms with vigour of mind and body, and advanced to the battle…

pedestris pugna par animis magis quam viribus erat, quas recentes Poenus paulo ante curatis corporibus in proelium attulerat; contra ieiuna fessaque corpora Romanis et rigentia gelu torpebant. restitissent tamen animis, si cum pedite solum foret pugnatum; sed et Baliares pulso equite iaculabantur in latera et elephanti iam in mediam peditum aciem sese tulerant et Mago Numidaeque, simul latebras eorum improvida praeterlata acies est, exorti ab tergo ingentem tumultum ac terrorem fecere.

The battle between the infantry was equal rather in courage than strength; for the Carthaginian brought the latter entire to the action, having a little before refreshed themselves, while, on the contrary, the bodies of the Romans, suffering from fasting and fatigue, and stiff with cold, were quite benumbed. They would have made a stand, however, by dint of courage, if they had only had to fight with the infantry. But the Baliares, having beaten off the cavalry, poured spears on their flanks, and the elephants had already penetrated to the centre of the line of the infantry; while Mago and the Numidians, as soon as the army had passed their place of ambush without observing them, starting up on their rear, occasioned great disorder and alarm.

Livy XXI, 54-55.

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

By Jove...

Today is the 2515th anniversary of the dedication of the temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill. Here are seven things you may not have known about Jupiter.

- His name isn’t really Jupiter- it’s Jove. Jupiter (Iuppiter in Latin) is derived from Iovis pater (father Jove).

- For the Romans he was the god of the sky (hence the thunder and lightening) and therefore the supreme god. He was also the patron god of Rome, and had the job of looking after laws and social order.

- His sacred bird was the eagle, and his favourite tree was the oak (though olive trees were sacred to him as well).

- He was married to Juno, who also happened to be his sister.

- One of his favourite tricks was to transform his appearance, and on different occasions he changed himself into a bull to seduce Europa, a shower of gold to seduce Danae, and a swan to seduce Leda.

- Jupiter had quite a lot of lovers. In fact the moons of the planet Jupiter (of which there are at least 63) have traditionally been named after his lovers, (such as Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto) and their descendants.

- The French word for Thursday (Jeudi) is named after Jupiter, coming from the Latin Iovis dies. The word Thursday comes from Thor- the Norse equivalent of Jupiter. In German, Thursday is Donnerstag after the thunder of Thor/Jupiter (donner means thunder, blitzen is lightening).

Thursday, August 24, 2006

On this day...

Here's an extract from Pliny the younger's famous description of the event, as he observed it from Misenum, across the bay from Pompeii:

iam cinis, adhuc tamen rarus. respicio: densa caligo tergis imminebat, quae nos torrentis modo infusa terrae sequebatur. ‘deflectamus’ inquam ‘dum videmus, ne in via strati comitantium turba in tenebris obteramur.’ vix consideramus, et nox - non qualis illunis aut nubila, sed qualis in locis clausis lumine exstincto.

audires ululatus feminarum, infantum quiritatus, clamores virorum; alii parentes alii liberos alii coniuges vocibus requirebant, vocibus noscitabant; hi suum casum, illi suorum miserabantur; erant qui metu mortis mortem precarentur; multi ad deos manus tollere, plures nusquam iam deos ullos aeternamque illam et novissimam noctem mundo interpretabantur. nec defuerunt qui fictis mentitisque terroribus vera pericula augerent... possem gloriari non gemitum mihi, non vocem parum fortem in tantis periculis excidisse, nisi me cum omnibus, omnia mecum perire misero, magno tamen mortalitatis solacio credidissem.

Ashes were already falling, not as yet very thickly. I looked round: a dense black cloud was coming up behind us, spreading over the earth like a flood. ‘Let us leave the road while we can still see, ‘I said, ‘or we shall be knocked down and trampled underfoot in the dark by the crowd behind.’ We had scarcely sat down to rest when darkness fell, not the dark of a moonless or cloudy night, but as if the lamp had been put out in a closed room.

You could hear the shrieks of women, the wailing of infants, and the shouting of men; some were calling their parents, others their children or their wives, trying to recognize them by their voices. People bewailed their own fate or that of their relatives, and there were some who prayed for death in their terror of dying. Many besought the aid of the gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left, and that the universe was plunged into eternal darkness for evermore… I could boast that not a groan or cry of fear escaped me in these perils, but I admit that I derived some poor consolation in my mortal lot from the belief that the whole world was dying with me and I with it.

Pliny the younger, Epistularum libri decem VI.20